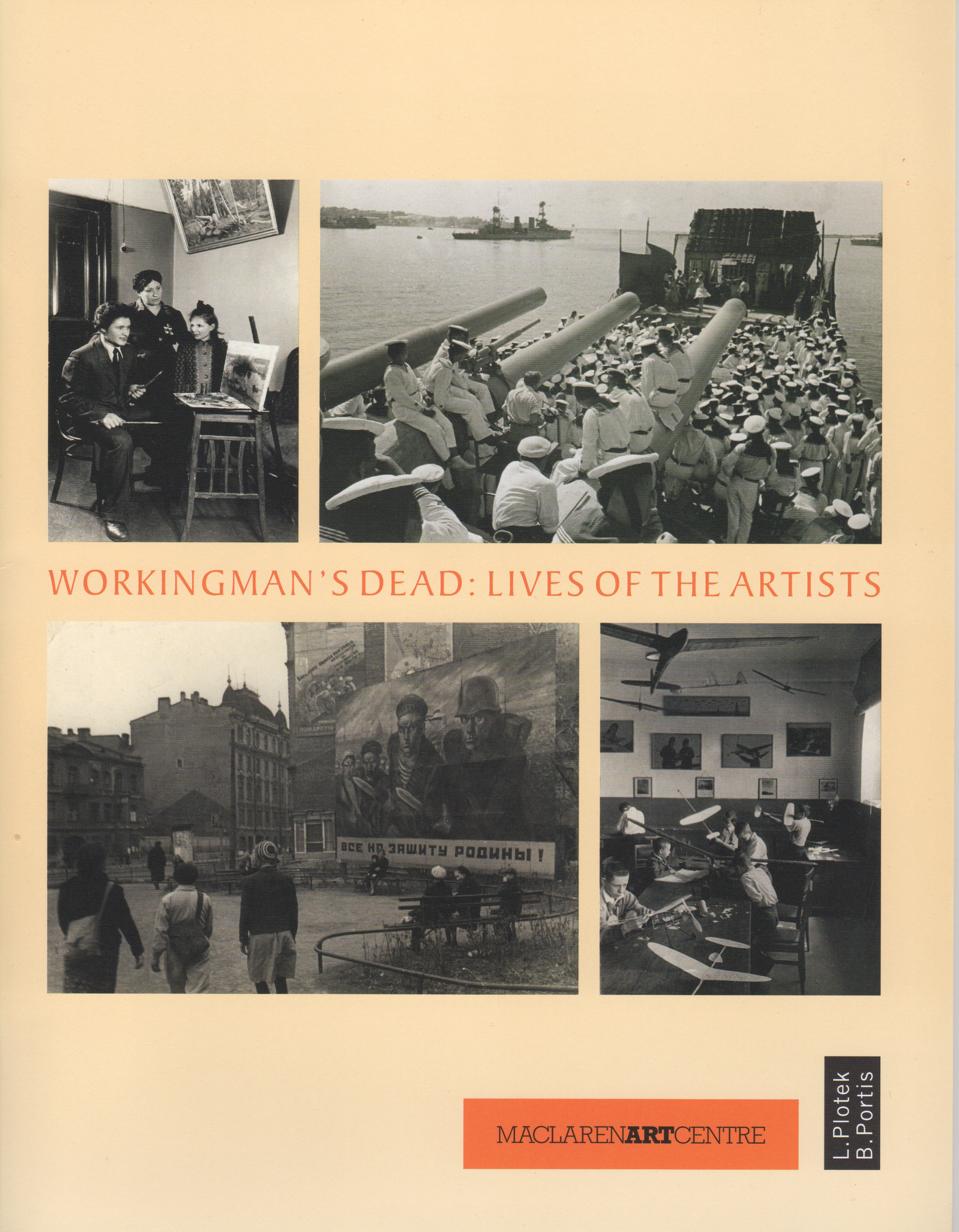

WORKING MAN'S DEAD: LIVES OF THE ARTISTS

by Ben Portis & Leopold Plotek

I can’t think of a painting of any importance I’ve ever done which had no subject. The subjects may have been as simple as the sight of a thing or a place, or as complex as a dramatic moment in history or myth,- but in every case they were the impulse under which a work got under way and which struggled for expression till the end. However, for some twenty-five years the starting image would be improvised on with great freedom, so that it might often be hard to pick out at first glance. Then, for the first five years of the century, I felt compelled for some reason,- and I still can’t say exactly by what,- to let the subject stand forth, unadorned. Like the elderly Ben Webster playing his tenor alongside the dizzying piano of Art Tatum, and simply shaping the tune, with a minimum of ornament or ‘commentary’: that’s how I needed these paintings to be. I felt, also, that I had to reinvent a kind of figurative style for each subject alone. Inevitably, dead painters, and their living works, lurked in the darker corners of the studio,- mostly 19th century heroes: Daumier, Delacroix, Corot. The paintings were elaborated without the aid of photographs. Not that I have any quarrel with photographs, it’s just that they have such iconic power that, once imposed on my mind’s eye, I can’t have the pleasure of imagining the subject with any freedom or conviction. And after all, truth and freedom are what the whole effort is about.

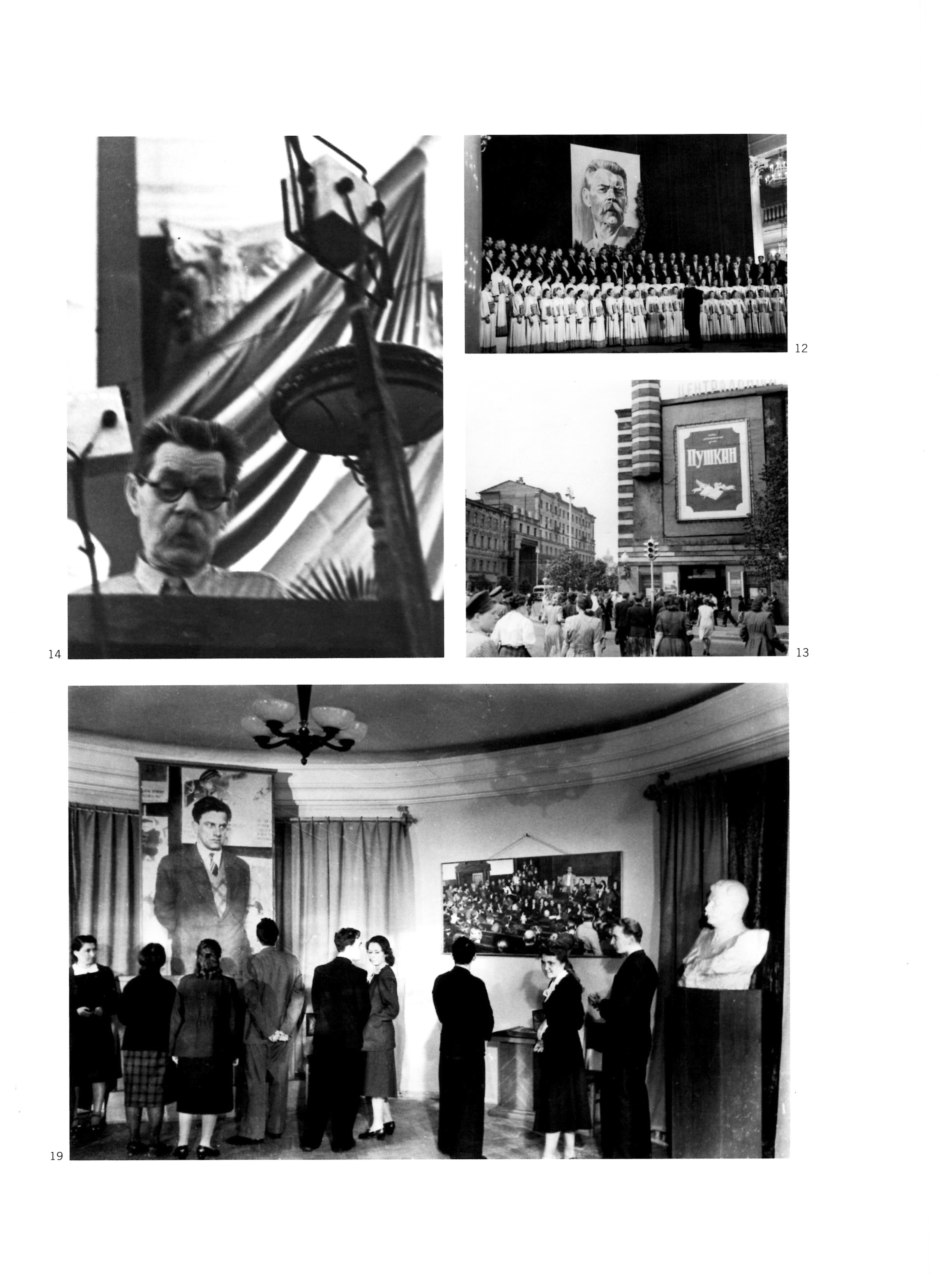

Once I’d begun, all kinds of subjects which had been dormant in my mind began to clamor for attention. Moments of operatic drama in the lives of artists were predominant: Joseph Conrad’s, or Sonny Rollins’s, or Veronese’s. And increasingly there came ‘Soviet’ subjects. No great surprise; born in Moscow just after the war to Jewish survivors, and into an atmosphere thick with Stalinist purges and paranoia, the shadowy dramas of that time and place have never left the background of my imagination. Many were reflections upon the terrible, impossible relation between artists and authority. ‘Speaking truth to power’ is a nice phrase but hard to live up to, and in Stalinist Russia it was a mortal risk. Geniuses like Mandelstam, Babel or Meyerhold paid with their lives, but others like Eisenstein, Shostakovich, Akhmatova, Malevich or Bulgakov paid with constant dread, betrayal, and a closeted, schizoid existence. Richly rewarded and celebrated for their ‘official’ works, their authentic art went unheard, unread and unseen. Not that the USSR had any kind of shortage of art; indeed, vast libraries, theatres and museums were filled, and an altogether new public was encouraged to use them. But what they were served with was the most tepid, formulaic, bourgeois stuff. This was indeed a reflection of the taste of the Supreme Critic, Joseph Stalin. Probably no political leader has meddled more deeply in the professional and private lives of artists. Stalin required not only that Soviet arts compete with their western counterparts while embodying the Party’s ideologicalpostures, but that the artists feel a genuine affection for himself. No wonder that the radical vitality of the Revolutionary years was soon frozen out by the increasingly rigid dictates of the leadership.

The Boss himself wrote unsigned reviews in the press, of literature, music, theatre and film, his favourite art. These could have a devastating effect, as Shostakovich discovered in 1937. Stalin slammed his new opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, for the sin of ‘formalism’,- which is to say a genuine effort to write fresh, living music. In fact his prudishness was also offended by the work’s sexual frankness. The fate of artists and artworks was, therefore, creepily intimate with the Fount of Aesthetic Judgment. But of course the degree of social control by the ‘organs’ of the Party over all areas of social life was without limit, and art was no exception.

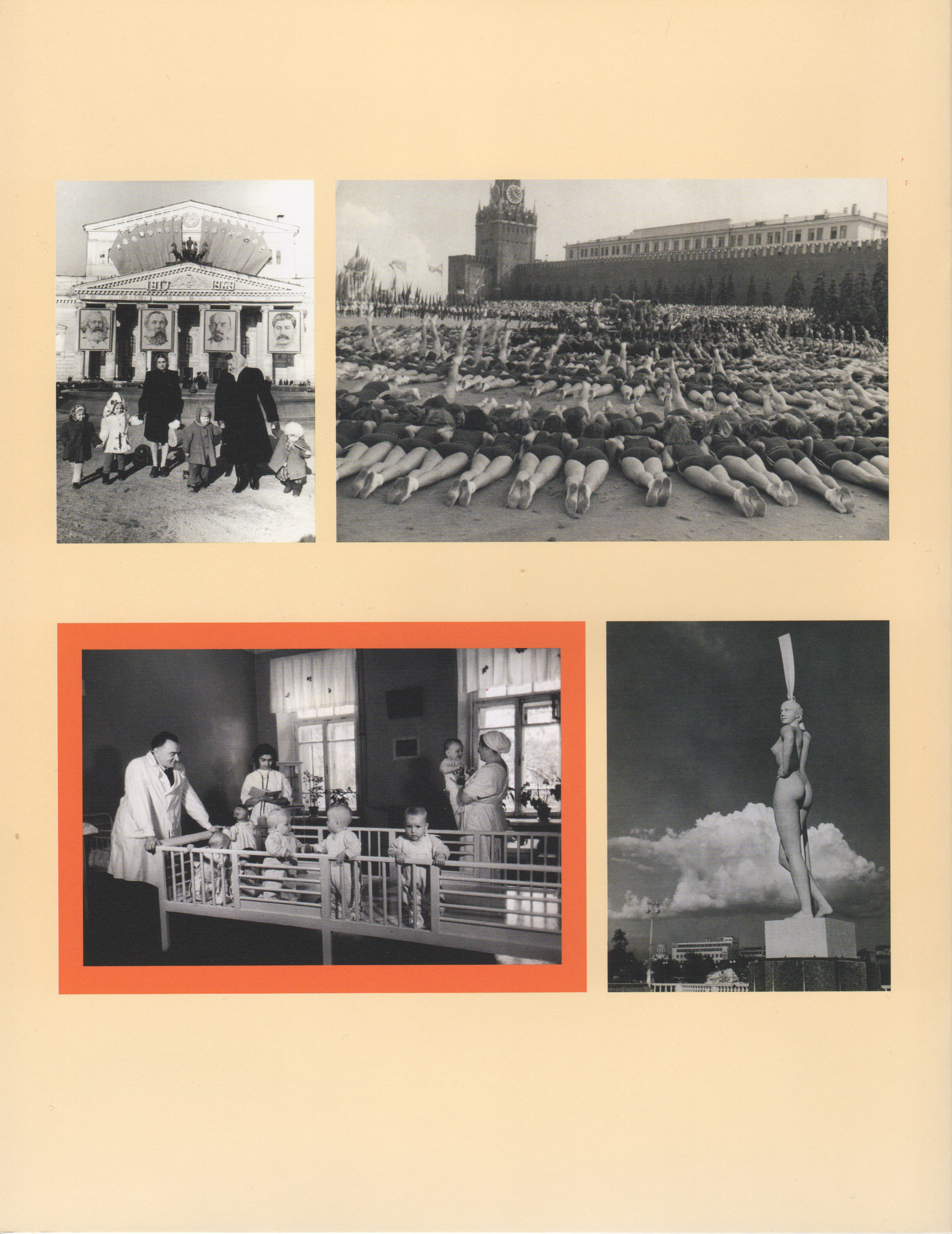

Ben Portis’sidea that we ought to hang some of my ‘Soviet’ paintings alongside a selection of documentary photographsfrom the official SOVFOTO archive was too tempting to resist. The apparent irony is actually superficial. In fact, the Russian photographers on the job, and I in my studio, were both inventing. Except that the inventions run at cross-purposes. The SOVFOTO archive was, of course, an instrument of propaganda meant to offer anodyne images of brave, cheerful, progressive Soviet life to the Press of a Cold-War enemy who was bent on demonizing it. Mind you, they’re mostly no less ‘realistic’ than Father Knows Best, or today’s reality-TV. The paintings I tried to make were efforts to cut through both distortions, to arrive at moments of authentic feeling. My engagement with them is rooted in a coincidence of birth, but my right to them is the right of any artist, and indeed of every human being.

Finally, I think it’s increasingly clear that, while the life of ‘the soul of Man under Socialism’, as Shaw put it, was no picnic, its life under the contemporary global art-marketplace carries its own moral risks and exacts its own compromises.

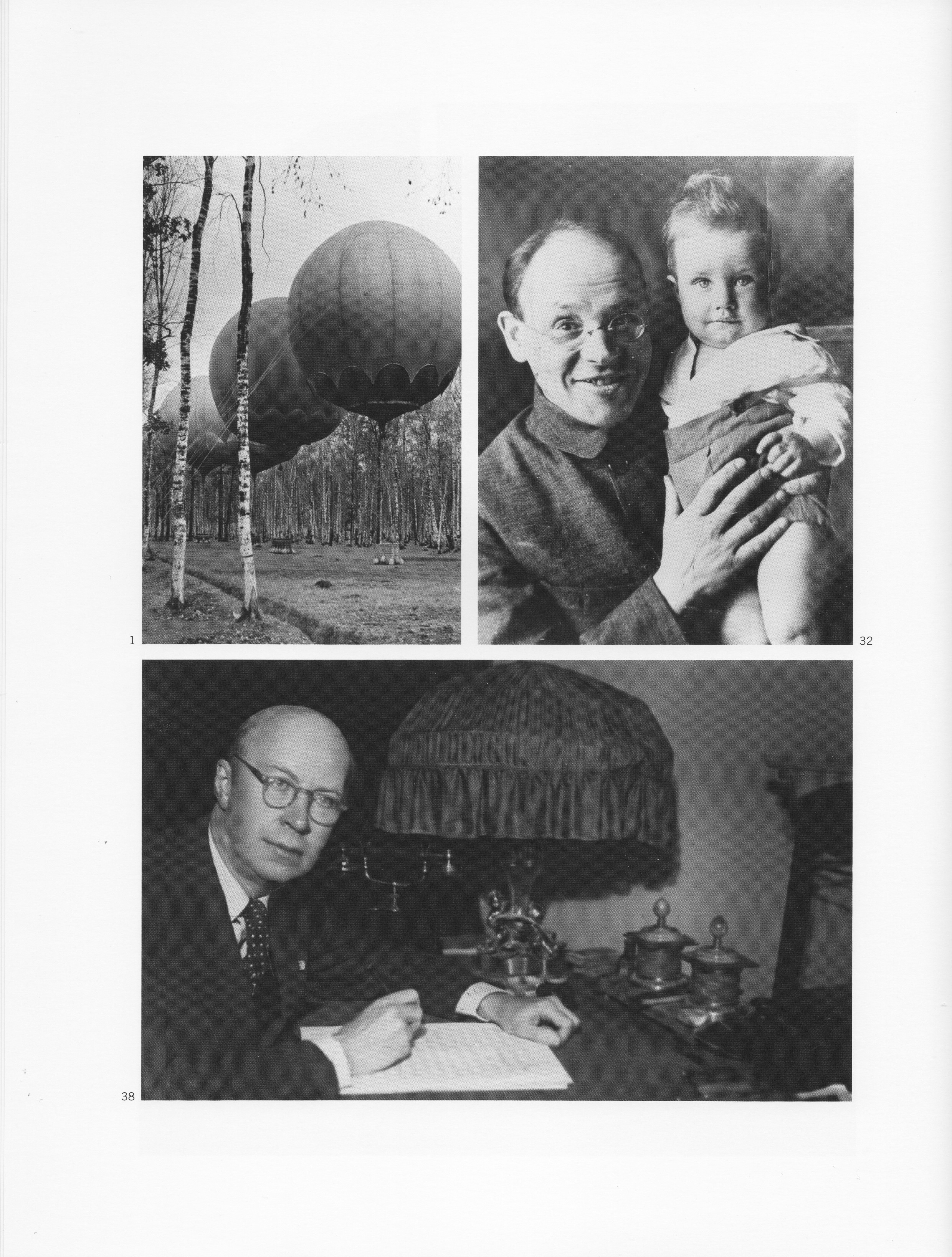

For some five years after 2000 I was obsessively painting a sequence of ‘history-paintings’, newly figurative depictions of dramatic moments mostly from the lives of artists, writers and musicians. Among these were a number of subjects drawn from Soviet history. It’s possible that their origin was my discovery that the Metropol Hotel in Moscow, where my parents were living in 1948, and in which I spent the first months of my life, was also the location (on another floor) of a suite of NKVD (later KGB) holding-cells, used to house political arrestees destined for trials and prisons elsewhere. The image of my nanny walking the hotel corridors holding my colicky infant-self, while the fancy elevators transported ‘zeks’ and their guards up and down, took a powerful hold on me.

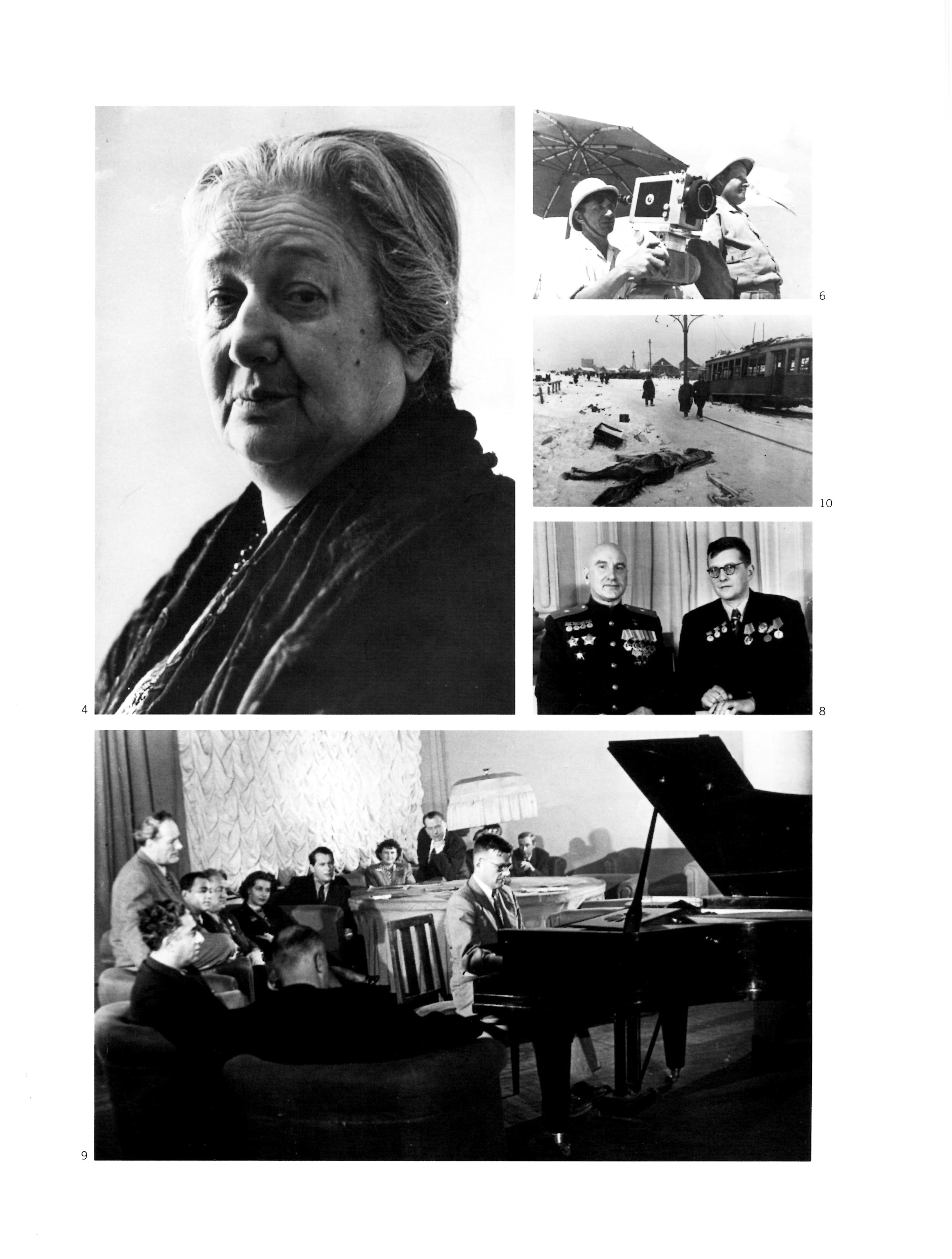

Eventually I made a number of paintings of episodes from the lives of Shostakovich, the poet Anna Akhmatova and the writer Isaac Babel. With the exception of the last (Babel was personally interrogated by the terrifying Lavrenty Beria and shot the following morning), they tend to have an edge of the absurd to them. Artists in the Stalinist USSR often had a bizarre relationship to Party discipline, and frequently to the Father of the Nation himself. Lionized and privileged for their ‘official’ productions, many created their authentic works ‘for the drawer’, in secret. The contradictions of their lives could have deadly consequences but also produced a wave of black humour.

We show here a number of these paintings alongside a selection from the MacLaren’s vast archive ofofficial SOVFOTOphotographs of the period, which were intended to project an image of modern, peace-loving, ‘normal’ Soviet life to the western press. For the duration of the War the two were temporary allies. But it’s worth pointing out, especially to younger visitors, that the Cold War period, when both sides lived with the permanent threat of ‘mutual assured destruction’ by nuclear weapons, was a time of vicious propaganda on both sides.

The paintings were created whole-cloth from my imagination, without the use of photographs. This has been the only way I can derive the challenge, and the pleasure, of bringing to life moments that continue to haunt and trouble me.

Soon after the October Revolution, the Imperial Eagle atop the Kremlin was replaced by a great red star. Modernity had come to Russia.

The great Bolshevik writer Isaac Babel was arrested and charged with treason. He was personally interrogated by Stalin’s chief prosecutor Lavrenty Beria and shot, the next morning, in the courtyard of the Lubyanka Prison.

Shostakovich was on a concert-tourof Siberia when he picked up a copy of the morning’s Pravda, to find a vicious review of his new opera by Stalin. For the next sixteen years his life would suffer an unpredictable succession of triumph and humiliation. Incidentally, after his music finally came to be performed in the West, he was condemned by many Western critics as ‘retrograde’ for the compromises he had been forced to endure.

During the terrible Nazi siege of Leningrad, in which a third of the population starved and froze to death, a troop of ‘artist-firefighters’ were taken to the roof of the Conservatoire to pose for a patriotic poster. I’ve seen the poster, but not before I had imagined, and painted, this portrait of Shostakovich.

Anna Akhmatova, Leningrad’s greatest poet, survived the siege of the city. Soon after the war, she was visited by Isaiah Berlin, the émigré Oxford intellectual. After tea, she insisted on reciting some verses of Byron in her mangled English, to Berlin’s great embarrassment. The visit drew the attention of the KGB, who redoubled their campaign of harassment against her.

Some years ago I discovered that in the Hotel Metropol in Moscow, where my parents lived at the time of my birth, the secret police occupied a floor which served as holding-cells for political prisoners on their way to the Gulag, or worse. I imagined being walked by my nanny in the halls of the hotel while men and women were transported to their fates in the elevator.

Hart Crane, one of the seminal voices of modern American poetry, jumped into the waters of the Atlantic on his return journey from self-imposed exile in Cuba to New York and to a vicious literary scene which he dreaded. His body was never recovered.

Sonny Rollins, the great tenor saxophonist, experienced a crisis of confidence after his early successes. He responded by relearning his instrument, and the jazz tradition, by playing nightly alone, for years, on the walkway of Willamsburg Bridge between Brooklyn and Manhattan.

John Donne, with Shakespeare one of the two most innovative poets of the English Renaissance, became a Churchman later in life. Sick with his final illness, and readying his soul for its passage, he commissioned a death-portrait of himself, for which he posed wrapped in his winding-sheet, in a room filled with incense smoke. The painting did not survive, but an alabaster statue from it surmounts his tomb in St. Paul’s.

This began as a scribble from a drawing by Domenico Tiepolo of Christ on the Sea of Galilee. The storm was compelling enough to start a painting, but all through the following weeks I imagined instead the gods of the ancient world sailing to their exile in a frail boat.

Doctor Samuel Johnson, wit, critic and probably my favourite English prose writer, died crushed by depression and an overwhelming sense of futility.

By the time his parents died, the great rationalist philosopher Spinoza was living humbly and writing, banished from the Jewish community of Amsterdam. Oddly, the sole object he chose to keep for himself from their estate was a collapsible canopy-bed they had carried to their own exile from Portugal,- and in which he had probably been conceived.

This painting began as a single shape: a shard of pottery from a Greek vessel in a small provincial museum. The image of a great eye,- like the Eye of Horus,- tipped on its side, took control and generated the rest of the canvas. The title, a play on the cliché meaning a noisy protest, or a ‘great fuss’, crossed with the name of a colour and stamped itself on the picture.

The rearview of the Monument to the German Soldier in the Berlin cemetery.

One night on his trek through the wilderness back to Egypt to begin his great mission, Moses is attacked with murderous fury, by God. His life is saved only by his quick-thinking wife, who circumcises their son and throws the bloody foreskin on the ground before the Almighty who, just as suddenly, retreats. A strange passage in Exodus, of which the rabbis have largely steered clear.

The only dream which the great critic recorded in full. He is wandering through a rich gallery of paintings when he is stopped short: a picture of a physician, in the act of disemboweling himself! Ruskin is frozen in dread, and awakes.

Albion Mills was the first mechanized textile mill in England. Its workers, fearing destitution at the loss of their jobs, burned the factory down. I imagined William Blake, then living in the neighbourhood, walking past its ruins.

Blake, laid-up in bed with a gravely injured leg, is visited by the teenaged Samuel Palmer, and gives the boy his blessing. Palmer grows up to become one of the most visionary, curious and beautiful painters to emerge in the England of the 19th century.

Blake as a small child in bed saw God looking in at his window, and was beaten for insisting it was true. I borrowed God’s face from my Hassidic fishmonger on St. Viateur Street in Montreal. It somehow seemed inevitable at the time.

______________________